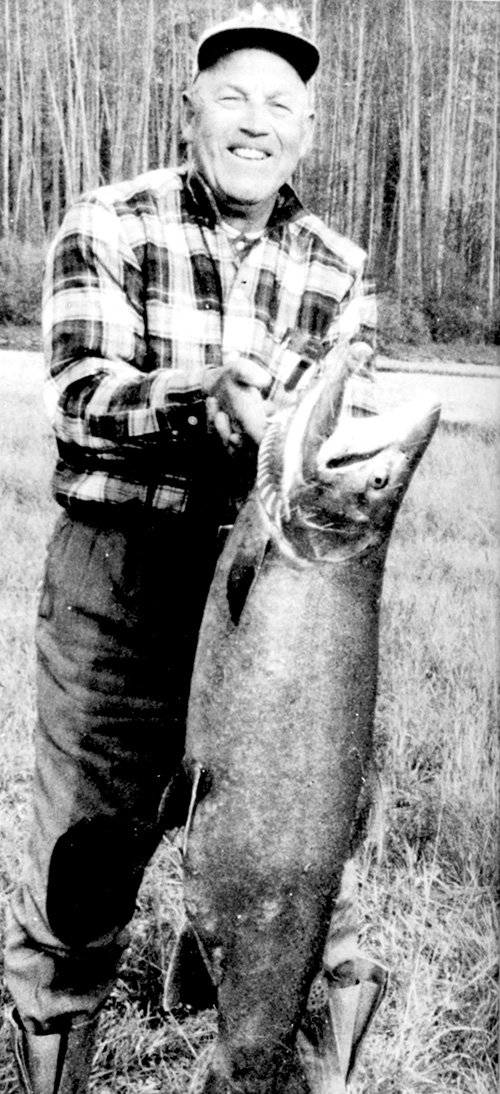

Karl Mausser At The Peak Of Catch & Kill

The picture was jaw dropping (pictured below). There’s a guy using both hands to hold up a huge fish. The caption says the fish is a Kispiox River steelhead, but it looks like it has grouper in its DNA, a giant-jawed monster from Oz that didn’t look like any torpedo-shaped steelhead I’d ever seen. Karl Mausser is identified as the conquering fly fisherman, and his 33-pound steelhead declared the largest ever taken on a fly. The International Game Fish Association also recognized the steelhead as a fly-fishing world record. The date of the catch was October 8, 1962. Mausser would later admit that the steelhead was so out of gas he’d booted it ashore.

During the late 1960s, I was nearing completion of a book about steelhead, its ocean migration and distribution, its life history, and something about fly fishing for them. Getting Mausser to say a few words about his steelhead would be an important addition to my first book. Locating him began in 1963 when Field & Stream magazine published winners of their annual fishing contest. I saw that Mausser was from Burlingame, California. After calling “information” and obtaining his phone number, I made the call and told him about my book. I hoped that this man now residing in the pantheon of fishing gods would deign to contribute to my little book. I pestered him with letters lavish with praise over his accomplishment of putting down such a monster steelhead. You know, something not for the faint of heart, a record that would stand for the ages, and so on. I meant every word and was truly in awe of this catch. The seduction worked.

Karl would send me some Kispiox flies that he’d personally tied, and he would send me a picture of his record steelhead that I could use to illustrate my book. I continued writing to him for more information until he asked if I’d like to join him for a few hours of fly fishing on Washington’s Kalama River. This was a late October pit stop he’d scheduled while trailering home from the Kispiox to his home in Burlingame, California. At the time, this invite was nothing less than being asked to be the fifth Beatle. I couldn’t sing any better than I could fly fish for steelhead, so I was at once elated and terrified. We made arrangements to meet at a general store well down the river road, and from there we’d go to a run of Karl’s choosing. He and his buddy—this may have been Roy Pitts—were camping on the Kalama, a minor league Columbia River tributary, for sure, nothing like the Skeena’s legendary big-league rivers where serious fly fishermen collected to hunt for the largest steelhead on earth.

I drove south from my home in Port Townsend and when I turned onto the river road I was dumbstruck. On my right was a telephone pole and stapled to it was that iconic picture of Mausser and his record steelhead. A few telephone poles farther down the road was another picture, and then another. Karl had served notice to this groupie and his fans that there was a rock star in town, and to see him I needed only to follow the pictures. There was an electricity in the air, and it was coming off my body.

I found Karl and his friend at the designated store, and after a brief meeting I followed them downriver to a lovely, long run. Karl insisted that I take the lead. He would watch my every cast. I put on my Herter’s waders and under his watchful eye I assembled my outfit. This is where the wheels of my little bandwagon began coming off.

As a college student living near Fenwick’s Long Beach, California, factory, I’d ordered the rod “in house” directly from Jim Green, the resident world champion distance caster, and though he tried to counsel me to purchase a 9- or 10-weight steelhead rod, I convinced him that in my Olympic Peninsula rivers, salmon and steelhead were man-eaters. I equated rods to rifle calibers. Something big bore meant big steelhead and salmon, and likely elevated levels of testosterone for the caster. Thus, when I rigged up to fish the Kalama, I was armed with a nine-foot 11-weight rod, a pole-vault stick balanced with the largest Pflueger Medalist reel, all in all, a great combination for tarpon in the Florida Keys. As I stepped into the river, massively prepared for any monster steelhead suicidal enough to mess with me, I was casting the latest in fly lines, a Scientific Anglers Wet Cell shooting head.

I should add that I could cast, double-hauling my shooting head across the river and sometimes into the trees. But what should take place after the cast still wasn’t finding a steelhead and explains why after thousands of casts, I’d caught a couple winter-run Hoh steelhead, and one of those was a jack; add to that a Deer Creek summer-run from the North Fork Stillaguamish. This scanty record wasn’t nearly enough to support my contention that I was a steelhead fly fisherman.

The river slowed on the lower part of the run and my fly was getting down into “the zone.” When the swing stopped, there was faint life, maybe a “grab,” or a “take”? Surely a take, I thought, and imagined something with big shoulders and full of steelhead fight. Here before the King of Giant Steelhead I’d hooked up and now it was plowing its way slowly down the run, becoming more powerful and determined as it swept its way into the tailout. When the fish reached the broken shallows, my rod took a nice bend, and my backing began to rapidly pay out. Karl saw all this and had walked to below me while I staggered and slipped on the rocks and followed my steelhead. I was elated; timing is everything.

The sluggish “run” suddenly stopped, and as my fly line washed into the shallows I began reeling in the slack line. Had my steelhead suddenly died from a mortal hook-up? Karl walked out to see what the fuss was all about. I could hear his hoots of derision over the sounds of the river. He called up to me, “You snagged a whitefish!”

When I reached my catch, I saw that the whitefish had rolled up on the leader until it could do nothing more than be carried downriver, a prisoner of the currents and my imagination.

I was mortified, exposed as a complete fraud, a man who’d missed the off-ramp to the Idiot’s Convention. There was just no dignity to be found anywhere in fighting a trash fish to the finish that was so wrapped up in my leader that I could just as well have been fighting a small sock and doing so with Karl Mausser looking down with barely concealed contempt.

Mercifully, the fishing was over for the day. I followed my companions to their campsite where I was not included in their conversation and used the opportunity to slink away. I needed some down time while I learned how to put on my big-boy waders. After wishing them good fishing, I left. I would never see Karl again.

History did not treat Karl Mausser well. Catch and release took hold and was embraced with a religious fervor. Even inbred hatchery fish that should have been killed were released. In the view of steelhead fly fishers, Mausser hadn’t caught a world record; he’d assassinated the beloved King of the Gene Pool. His catch of a lifetime was viewed with ever-increasing contempt. To underscore his place in this new fishing paradigm, Mausser’s 33-pound steelhead became the ultimate catch to release. Fly-caught steelhead were carefully measured, their girth and length run through a formula that gave the fisherman a fairly accurate weight. A picture taken of the angler kneeling in the river, the steelhead partially submerged so no injury would occur—a steelhead weighing 33 pounds or more—became the ultimate record, a mocking validation that Mausser’s record was forever safe. No steelhead fly fisher would dare break a record that had become a shameless stain on our sport.

Karl was critically aware of this and became increasingly bitter over what had made him a folk hero in 1962 was an act of treason 10 years later. Late in life he allegedly regretted he’d ever killed the steelhead. In this regard, our sport of fly fishing for steelhead had become unforgiving; there would never be redemption for killing a giant wild steelhead.

Author’s Note: Mausser’s steelhead could have weighed 40 pounds when it threaded the miles of coastal gillnets and Prince Rupert’s gillnets set off the Skeena and began its return to the Kispiox, over 300 miles into British Columbia’s interior. That fact underscores that despite many protections sponsoring their survival, the ever more rare giants are still caught in ocean gillnets and in gillnets set by Native Americans on the west side of the Olympic Peninsula. There’s no doubt that the trend line isn’t going up anywhere. Idaho’s famous “B” run steelhead has been genetically savaged where the very largest fall prey to gillnets set by Indians above Bonneville Dam for Chinook salmon. These Clearwater River hatchery steelhead have now been recycled for forty years, but wild steelhead were never intentionally part of the breeding program. Fishery biologists will tell you that these steelhead have become progressively smaller. Large is relative; today a Clearwater steelhead 34 inches long is “large.” Fly fishermen most certainly support that contention.

There are on Washington’s west coast two watersheds, the Sol Duc and the Quinault. Back in the 1960s I would occasionally see a picture of a huge steelhead taken in a Quinault gillnet, bragging rights for the tribe, but I don’t see that anymore.

The image of a steelhead that haunts me still is a Thompson buck I saw dragged out of the river by a bait fisherman many years ago. The fish was beyond believable, a size I never imagined a steelhead could reach. Any claim of mine as to its size would mark me a liar by most. But I can say that this over-40-pound white and gray steelhead was as handsome as it was enormous, a steelhead for the ages, and one that no angler could ever boot to the beach.

As the years have passed, I ever more keenly see that this one steelhead that brought such size and vitality to the entire race of Thompson was in fact why they’re such an extraordinary race. The loss of that single steelhead took the Thompson race much closer to extinction. Today the river is closed to fishing as the handful of steelhead reach the edge of oblivion and still cannot find protection under Canada’s Species at Risk Act.

Karl Mausser holds his 33-pound world record. The huge dark buck struck a Kispiox Special.